Imagine stepping onto your patio or balcony and plucking a ripe, juicy apple or a sweet fig directly from a tree you grew yourself. This dream is entirely achievable, even if your garden space is limited to a small balcony or a cozy patio. Dwarf fruit trees offer an incredible opportunity to enjoy homegrown produce, transforming confined urban spaces into productive edible oases. These compact versions of traditional fruit trees thrive in containers, bringing the joy of an orchard to your doorstep without requiring vast acreage.

Growing your own fruit offers numerous rewards. You gain control over what goes into your food, enjoy the freshest possible taste, and connect with nature on a daily basis. For small-space gardeners, selecting the right dwarf fruit trees and providing them with proper care makes all the difference. This comprehensive guide equips you with the knowledge and practical steps to successfully cultivate a mini-orchard of container fruit trees, ensuring bountiful harvests for years to come.

Why Choose Dwarf Fruit Trees for Small Spaces?

Dwarf fruit trees are a game-changer for anyone gardening with limited room. Their primary advantage lies in their compact size, typically reaching heights of 6 to 10 feet when mature, making them perfectly suited for containers on patios, balconies, or small urban yards. You gain all the benefits of growing fruit without needing a large plot of land. These trees often produce fruit at a younger age than their standard counterparts, sometimes within one to two years of planting, giving you quicker gratification for your gardening efforts.

Setting up your vertical or container garden correctly from day one helps you avoid common balcony garden mistakes that many beginners encounter.

Beyond their size, dwarf fruit trees offer incredible flexibility. You can move them to optimize sun exposure throughout the day or shift them indoors during harsh winter weather. This portability proves invaluable for protecting your investment from extreme conditions. Moreover, tending to container fruit trees is physically less demanding. You work at a comfortable height, simplifying tasks like pruning, watering, and harvesting. This accessibility makes fruit growing enjoyable for gardeners of all ages and physical abilities.

Consider the environmental benefits as well. Growing your own fruit reduces your carbon footprint by minimizing transportation and packaging. You also support local pollinator populations by providing nectar sources, contributing to a healthier ecosystem right outside your door. Many gardeners find immense satisfaction in nurturing a living plant from bloom to harvest, fostering a deeper connection with nature and the food they consume.

Understanding Dwarf vs. Standard Fruit Trees

The key distinction between dwarf and standard fruit trees lies in their rootstock. Most fruit trees are grafted, meaning a desired fruiting variety (scion) is joined onto a root system (rootstock) from another plant. The rootstock largely determines the tree’s ultimate size, disease resistance, and adaptability to soil conditions. Standard rootstocks produce full-sized trees that can reach 20 feet or more, requiring significant space and making harvesting difficult without specialized equipment.

Dwarf fruit trees, conversely, utilize dwarfing rootstocks. These rootstocks inhibit vigorous growth, keeping the tree compact while allowing the scion to produce full-sized fruit. For example, an apple tree grafted onto a M27 or B9 rootstock will remain small, typically 6-8 feet tall, compared to an apple tree on a standard rootstock which might grow to 25 feet. This genetic engineering allows you to enjoy Gala or Honeycrisp apples from a tree no taller than you are.

Here is a comparison outlining the practical differences:

| Feature | Dwarf Fruit Trees | Standard Fruit Trees |

|---|---|---|

| Mature Height | Typically 6-10 feet | 15-30+ feet |

| Space Requirement | Small, ideal for containers, patios, balconies | Large garden plots, orchards |

| Fruiting Age | Often 1-3 years after planting | 3-7+ years after planting |

| Maintenance | Easier to prune, spray, and harvest due to height | Requires ladders or specialized equipment for maintenance |

| Portability | Can be moved, brought indoors for winter | Stationary, cannot be moved |

| Rootstock | Dwarfing rootstocks (e.g., M27, B9 for apples) | Vigorous rootstocks |

| Lifespan | Generally shorter (15-25 years) | Longer (30-50+ years) |

| Yield per Tree | Lower than standard, but multiple trees fit in small space | High per tree, but fewer trees overall |

Understanding these differences empowers you to make an informed choice for your specific gardening needs and available space. Dwarf fruit trees are not simply smaller versions of their larger relatives; they represent a distinct category with specific advantages for container gardening.

Selecting the Best Dwarf Fruit Tree Varieties for Containers

The success of your container fruit orchard begins with choosing the right trees. Factors such as your USDA plant hardiness zone, available sunlight, and the tree’s pollination requirements all play crucial roles. Most fruit trees need at least 6-8 hours of direct sunlight daily to produce fruit. Check if your chosen variety is self-fertile or requires a pollinator. Some trees, like many apple and pear varieties, need a different variety planted nearby to produce fruit.

To make the most of your space, consider using companion planting for small spaces at the base of your tree containers.

Top Dwarf Fruit Tree Varieties for Patios and Balconies:

- Dwarf Apple Trees: Look for varieties on ultra-dwarfing rootstock (like M27 or B9). Popular choices include ‘Honeycrisp’, ‘Gala’, ‘Fuji’, and ‘Granny Smith’. Many require a second apple variety for cross-pollination.

- Dwarf Pear Trees: ‘Dwarf Anjou’ and ‘Dwarf Bartlett’ are excellent choices. Pears often need a pollinator, so consider planting two different compatible varieties.

- Dwarf Peach and Nectarine Trees: Self-fertile varieties like ‘Bonanza’ peach or ‘Necta Zee’ nectarine are ideal. They are bred specifically for compact growth and heavy fruit production in small spaces.

- Dwarf Cherry Trees: ‘North Star’ and ‘Romeo’ are self-fertile tart cherries that do well in containers. Sweet cherries often require a pollinator.

- Fig Trees: Figs are incredibly well-suited for containers and are generally self-fertile. Varieties like ‘Brown Turkey’, ‘Chicago Hardy’, and ‘Black Mission’ thrive and produce abundant fruit. You can often move them indoors for winter in colder climates.

- Dwarf Citrus Trees: Lemons (‘Meyer Lemon’), limes, oranges, and kumquats are excellent container fruit trees. They are self-fertile and bring an exotic touch to your patio. In most zones, they require winter protection indoors.

- Pomegranate Trees: Dwarf varieties like ‘Nana’ are ornamental and fruit-bearing. They tolerate heat and some drought, making them suitable for sunny, warm patios. They are self-fertile.

- Blueberry Bushes: While technically shrubs, dwarf blueberry varieties like ‘Top Hat’ or ‘Sunshine Blue’ are perfect for containers. Blueberries require acidic soil (pH 4.5-5.5) and often produce better with a second variety for cross-pollination.

- Mulberry Trees: Dwarf varieties like ‘Issai’ or ‘Gerardi Dwarf’ are productive and easy to grow. They are self-fertile and produce sweet, blackberry-like fruit.

When purchasing, select a healthy specimen from a reputable nursery. Look for strong, evenly spaced branches, healthy foliage, and no signs of pests or diseases. A vigorous root system is key for containerized plants, so check the drainage holes if possible. Avoid trees with circling roots or those that appear pot-bound.

Choosing the Right Container and Potting Mix

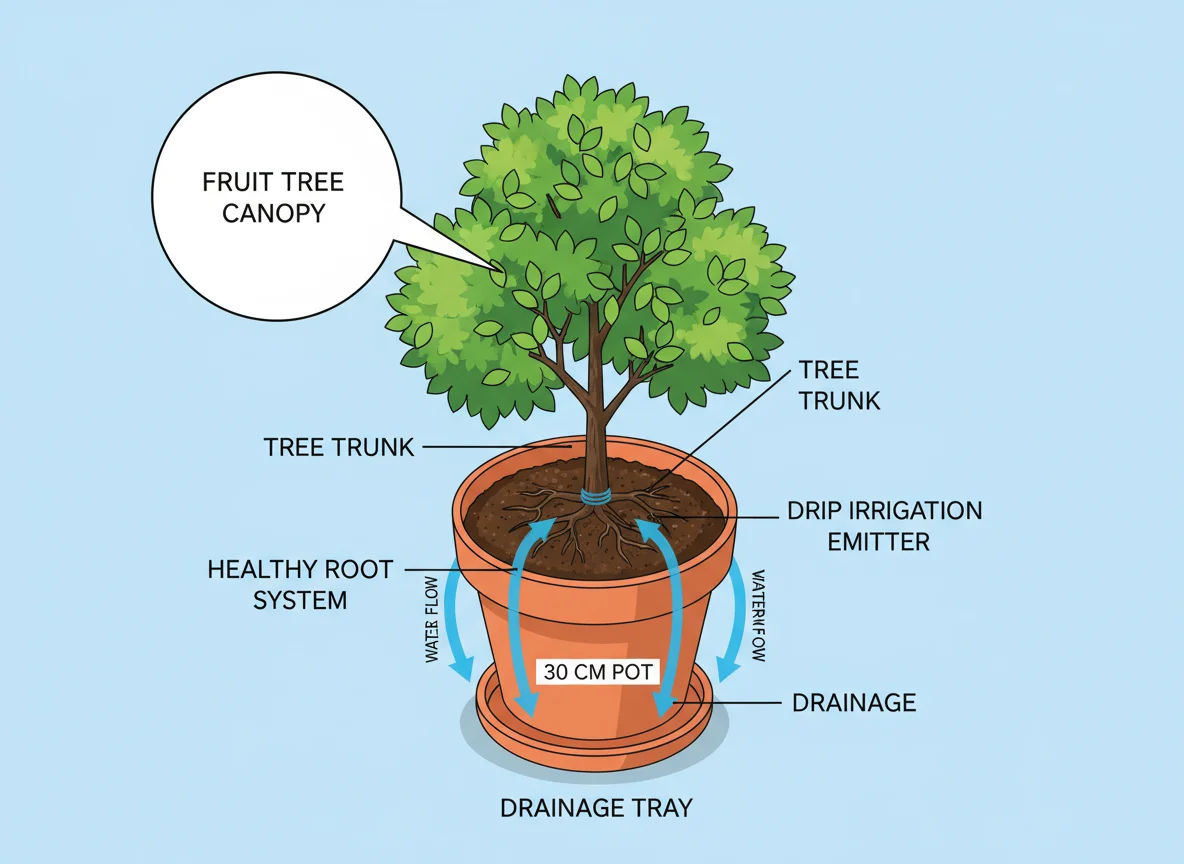

The success of your dwarf fruit tree depends heavily on its home. Selecting the correct container size and material, along with a high-quality potting mix, provides the essential foundation for healthy growth and prolific fruiting.

Container Selection:

Start with a container that is appropriately sized for your young tree, but plan to repot as it grows. A 10-15 gallon pot (around 18-20 inches in diameter) works well for a young dwarf tree. Within 2-3 years, you will likely need to move it to a 20-25 gallon container (24-30 inches in diameter). The final pot size should be at least 25 gallons, and some larger dwarf varieties, like apples or pears, may benefit from 30-gallon or even half-whiskey barrel-sized containers. The larger the pot, the more stable the root temperature and moisture levels will be, reducing watering frequency.

- Material Matters:

- Terracotta or Clay: These are attractive and allow excellent air circulation to the roots, which helps prevent root rot. However, they are heavy, dry out quickly, and can crack in freezing temperatures.

- Plastic: Lightweight, affordable, and retains moisture well. Look for sturdy, UV-resistant plastic to prevent degradation. Choose lighter colors to reflect heat and prevent roots from overheating in direct sun.

- Wood (Whiskey Barrels): Visually appealing and offers good insulation. Ensure the wood is untreated or treated with food-safe materials. These are heavy and durable.

- Fabric “Grow Bags”: Excellent for root health, preventing root circling, and promoting air pruning. They are lightweight, flexible, and offer superior drainage. They do dry out faster than plastic pots.

- Drainage is Non-Negotiable: Every container must have ample drainage holes at the bottom. Fruit trees absolutely cannot tolerate standing water, which leads to root rot. If your pot does not have enough holes, drill more.

Potting Mix for Edibles:

Do not use garden soil in containers; it compacts, lacks drainage, and often harbors pests and diseases. Instead, use a high-quality, well-draining potting mix specifically formulated for containers. Opt for peat-free or coir-based mixes to promote sustainable gardening practices. A good potting mix provides aeration, retains moisture, and supplies initial nutrients.

You can create your own robust potting mix by combining the following:

- 40-50% high-quality peat-free potting mix: This forms the base.

- 30-40% compost: Adds essential nutrients, beneficial microbes, and improves water retention. Use well-rotted, mature compost.

- 10-20% perlite or coarse sand: Enhances drainage and aeration, preventing compaction.

- Slow-release organic fertilizer: Incorporate according to package directions to provide sustained nutrition.

This customized blend ensures your container fruit trees receive the ideal environment for root development and nutrient uptake. For blueberries, adjust the mix to be more acidic, incorporating pine bark fines or specific acidic potting mixes.

Planting Your Dwarf Fruit Tree: A Step-by-Step Guide

Proper planting sets the stage for a healthy, productive tree. Follow these steps carefully to ensure your dwarf fruit tree establishes successfully in its new container home.

Timing is crucial for establishment; our spring planting guide for container gardeners offers specific tips for starting your mini-orchard during the growing season.

- Prepare Your Container: Place a piece of mesh screen or a coffee filter over the drainage holes to prevent soil loss while allowing water to escape freely. Do not add gravel or broken pottery at the bottom; this actually impedes drainage and creates a perched water table, which can lead to root rot.

- Add Potting Mix: Fill the container with a few inches of your chosen potting mix. Create a small mound in the center.

- Inspect the Tree: Carefully remove the tree from its nursery pot. Gently loosen any circling roots at the bottom of the root ball with your fingers. If the roots are severely root-bound, you may need to make a few vertical cuts down the sides of the root ball to encourage outward growth.

- Position the Tree: Place the tree on the mound of soil in the container. The goal is to ensure the graft union (the swollen knob where the scion meets the rootstock, usually a few inches above the soil line) remains above the soil surface. This prevents the scion from developing its own roots, which would negate the dwarfing effect of the rootstock. Adjust the soil level so the graft union sits 1-2 inches above the final soil line.

- Fill with Potting Mix: Backfill around the root ball with more potting mix, gently tamping it down to remove large air pockets. Leave about 1-2 inches of space between the soil surface and the rim of the container. This “head space” is crucial for efficient watering, allowing water to soak in rather than run off.

- Water Thoroughly: Water the tree slowly and deeply until water drains freely from the bottom of the pot. This settles the soil around the roots and eliminates any remaining air pockets. You may need to add a little more potting mix after the initial watering if the soil settles significantly.

- Stake if Necessary: Young dwarf fruit trees, especially those on very dwarfing rootstocks, can be top-heavy or have weak trunks. Insert a sturdy stake close to the trunk, taking care not to damage the root ball, and loosely tie the tree to the stake with soft material (such as old strips of cloth or specialized tree ties) to provide support during its first year of establishment.

Place your newly planted dwarf fruit tree in its final sunny location. Provide consistent moisture during the establishment phase, which typically lasts several weeks to a few months. Remember, the first few months are critical for root development and overall plant health.

Essential Care: Watering and Fertilizing for Fruitful Harvests

Consistent watering and appropriate fertilization are the cornerstones of successful container fruit tree cultivation. Because they are confined to a pot, these trees rely entirely on you for their nutritional and hydration needs.

During peak temperature months, beating summer heat stress is vital for preventing fruit drop and keeping your trees hydrated.

Watering Rhythm:

Container plants dry out much faster than those planted in the ground. You must check the soil moisture frequently. Stick your finger 2-3 inches into the potting mix; if it feels dry, it is time to water. Do not wait until the leaves wilt, as this stresses the tree.

- Deep Watering: When you water, do so thoroughly until water drains from the bottom of the pot. This encourages deep root growth and flushes out accumulated salts. Watering lightly and frequently leads to shallow root systems, making the tree more susceptible to drought stress.

- Frequency: In hot, sunny, or windy conditions, you might need to water daily or even twice a day. During cooler weather or after rainfall, you may water every few days. The size of your pot and the tree’s stage of growth also influence frequency. Larger pots retain moisture longer.

- Monitor and Adjust: Pay close attention to your tree and its environment. A moisture meter can provide a more accurate reading than just your finger, especially for larger pots.

- Sustainable Watering: Consider using a drip irrigation system with a timer for multiple container plants. This delivers water directly to the root zone, reducing evaporation and ensuring consistent moisture. Collecting rainwater for irrigation is another excellent sustainable practice.

Fertilizing for Success:

Container potting mixes typically have limited nutrients. Therefore, regular fertilization becomes essential for fruit production. Aim for a balanced organic fertilizer, or one slightly higher in phosphorus and potassium for fruiting, rather than nitrogen which promotes leafy growth.

- Early Spring: Apply a balanced slow-release organic granular fertilizer or a liquid feed once new growth begins. Follow the product’s instructions for dosage.

- Late Spring/Early Summer: Reapply a lighter dose of fertilizer, especially if you see signs of nutrient deficiency (yellowing leaves, poor growth).

- Avoid Late Season Fertilization: Stop fertilizing by late summer or early fall. New growth stimulated by late-season fertilizer applications may not harden off before winter, making it vulnerable to frost damage.

- Compost Tea and Worm Castings: Supplement your feeding regimen with compost tea or a top dressing of worm castings. These provide a gentle, slow release of nutrients and introduce beneficial microbes to the soil, improving overall soil health.

- Specific Needs: Blueberries require acidic fertilizers, often containing ammonium sulfate or specific “acid-loving plant” formulas. Citrus trees benefit from specialized citrus fertilizers that contain micronutrients like iron and zinc.

Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions for any fertilizer product you use. Over-fertilizing can harm your tree, leading to burnt roots or excessive vegetative growth at the expense of fruit.

Pruning and Training for Health and Yield

Pruning is not about removing branches; it is about shaping your dwarf fruit tree, promoting health, and maximizing fruit production. For container fruit trees, pruning also helps manage size, keeping them compact and aesthetically pleasing for your patio or balcony.

Using specialized affordable garden gadgets like precision snips can make these maintenance tasks much more manageable for small-space owners.

The Goals of Pruning:

- Maintain Size: Keep the tree at a manageable height and width for container growing.

- Promote Air Circulation and Light Penetration: Remove crossing or overcrowded branches to allow light and air into the canopy, reducing disease risk and improving fruit quality.

- Remove Dead, Diseased, or Damaged Wood: Prevent the spread of disease and encourage new, healthy growth.

- Encourage Fruit Production: Prune to stimulate the development of fruiting spurs (short branches that bear fruit) or to encourage new growth that will fruit in subsequent seasons.

- Shape the Tree: Create an open, vase-like shape or a central leader system, depending on the tree type and your preference.

When to Prune:

The timing of pruning depends on the type of fruit tree:

- Deciduous Fruit Trees (Apples, Pears, Peaches, Plums): The best time for major structural pruning is in late winter or early spring, before new growth begins but after the threat of severe frost has passed. This allows you to see the tree’s structure clearly. Summer pruning can be done to control size or remove water sprouts, but avoid heavy summer pruning as it can reduce the current year’s crop.

- Evergreen Fruit Trees (Citrus, Figs, Olives): Prune these as needed to maintain shape, remove dead wood, or thin the canopy. Generally, light pruning can occur any time, but heavier pruning is best done after harvesting or during their dormant period, typically late winter or early spring.

Basic Pruning Techniques:

- Thinning Cuts: Remove an entire branch back to its point of origin or to another main branch. This opens up the canopy and encourages fruit production on remaining branches.

- Heading Cuts: Shorten a branch, cutting just above a bud or side branch. This encourages bushier growth and can stimulate the formation of fruiting wood.

- Remove Suckers and Water Sprouts: Suckers grow from the rootstock below the graft union; water sprouts are vigorous, vertical shoots that grow from main branches. Both consume energy without producing good fruit and should be removed as soon as you see them.

Always use sharp, clean pruning shears to make clean cuts. Sterilize your tools with rubbing alcohol between trees to prevent disease transmission.

Training Your Tree:

Training refers to guiding the tree’s growth into a desired shape. For container fruit trees, this often means encouraging an open, strong structure. Spreading branches horizontally can encourage more fruit production than vertical growth. You can gently tie branches down with soft ties or use branch spreaders to achieve this.

For research-based guidance on pruning, visit

Missouri Botanical Garden Extension or

USDA ARS Fruit Tree Pruning.

Pest and Disease Management for Container Trees

Even in a small space, your dwarf fruit trees can encounter pests and diseases. The good news is that container gardening offers advantages for managing these issues. Your trees are more accessible for close inspection, and their limited numbers mean you can often address problems quickly and effectively without resorting to harsh chemicals. Employ an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach, focusing on prevention and early intervention.

Prevention is Key:

- Healthy Trees: A healthy, well-nourished tree is more resistant to pests and diseases. Provide optimal watering, fertilization, and sunlight.

- Inspect Regularly: Make it a habit to inspect your trees weekly. Look under leaves, along stems, and at new growth for any signs of trouble. Early detection allows for easier control.

- Good Sanitation: Remove any fallen leaves, fruit, or debris from around the base of the tree and from the container. This eliminates potential hiding spots for pests and fungal spores.

- Quarantine New Plants: Before introducing any new plants to your patio, keep them separate for a week or two to ensure they are pest- and disease-free.

- Encourage Beneficial Insects: Plant pollinator-friendly flowers nearby. Ladybugs, lacewings, and parasitic wasps are natural predators that help control common pests like aphids.

- Provide Air Circulation: Proper pruning, as discussed, ensures good air flow through the canopy, which helps prevent fungal diseases like powdery mildew.

Common Pests and Solutions:

- Aphids: Small, pear-shaped insects that cluster on new growth, sucking plant sap. They cause distorted leaves.

- Solution: Blast them off with a strong stream of water, crush them by hand, or apply insecticidal soap.

- Spider Mites: Tiny, almost invisible arachnids that cause stippling on leaves and fine webbing. They thrive in hot, dry conditions.

- Solution: Increase humidity, spray leaves with water, or use insecticidal soap or neem oil.

- Scale Insects: Small, immobile bumps on stems and leaves, often covered by a protective shell. They also suck plant sap.

- Solution: Scrape them off with a fingernail or soft brush, or apply horticultural oil during dormancy.

- Fruit Worms/Maggots: Larvae that tunnel into developing fruit.

- Solution: Use floating row covers to exclude adult insects, or employ pheromone traps. Practice good sanitation by removing infested fruit.

Common Diseases and Solutions:

- Powdery Mildew: White, powdery spots on leaves and stems.

- Solution: Improve air circulation, apply neem oil or a horticultural fungicide.

- Leaf Spot (various fungi): Dark spots on leaves, often leading to defoliation.

- Solution: Remove affected leaves, improve air circulation, and practice good sanitation. Fungicides can be used in severe cases.

- Root Rot: Caused by overwatering or poor drainage. Leaves may yellow, wilt, and the tree declines.

- Solution: Ensure excellent drainage in your container. Allow soil to dry slightly between waterings.

Always identify the specific pest or disease before applying any treatment. Organic solutions like neem oil, horticultural oil, and insecticidal soaps are generally safe and effective when used correctly. Read product labels carefully and apply according to instructions.

Overwintering Your Patio Fruit Trees

For gardeners in regions with cold winters, protecting your container fruit trees from freezing temperatures is paramount. Unlike trees planted in the ground, which benefit from the insulating properties of surrounding soil, containerized trees have exposed root systems vulnerable to freezing and thawing cycles. Your overwintering strategy depends on your climate zone and the cold hardiness of your specific fruit tree.

If you are new to this, follow a dedicated guide to your potted orchard’s first winter to ensure your trees survive the cold safely.

Managing the cold requires specific tactics, so you may want to review how to prepare your potted orchard for winter to ensure your trees return stronger next spring.

Hardy Deciduous Trees (Apples, Pears, Cherries, Peaches):

If you live in a zone where your tree is hardy (e.g., a Zone 5 tree in Zone 5), but you grow it in a container, its roots are still more vulnerable than if planted in the ground. The general rule is that a container plant’s effective hardiness zone is two zones colder than its actual hardiness. A Zone 5 tree in a pot essentially becomes a Zone 7 tree in terms of root hardiness.

- Insulate the Pot: Wrap the container with burlap, bubble wrap, or blankets. You can also place the pot inside a larger insulated container, filling the gap with straw or leaves.

- Group Pots: Cluster your container trees together against a warm wall of your house. This creates a microclimate and provides collective insulation.

- Move to a Sheltered Location: Shift trees to an unheated garage, shed, or covered porch once temperatures consistently drop below freezing. They need protection from wind and direct freezing. Ensure they receive some light if possible, though dormancy means less light is needed.

- Minimal Watering: While dormant, trees need far less water. Check the soil every few weeks and water lightly only if the top few inches are dry. Do not let the pot dry out completely, but avoid overwatering.

Less Hardy or Evergreen Trees (Citrus, Figs, Pomegranates, some Mulberries):

These trees require more significant protection in zones colder than their hardiness rating.

- Bring Indoors: The safest option is to bring these trees indoors before the first hard frost.

- Location: Choose a bright, cool spot if possible (50-60°F or 10-15°C). An unheated sunroom, cool greenhouse, or a south-facing window in a cool room works well.

- Humidity: Indoor air can be very dry. Provide humidity with a pebble tray (a tray filled with pebbles and water, ensuring the pot sits above the water level) or a humidifier.

- Pest Watch: Indoor conditions can sometimes encourage pests like spider mites. Inspect trees carefully before bringing them inside and monitor them regularly throughout winter.

- Watering: Water less frequently indoors, allowing the top few inches of soil to dry out between waterings.

- Dormancy for Figs: Some fig varieties are hardy, but in colder zones, they can be brought indoors into an unheated garage or basement where they will go fully dormant. They lose their leaves and require very little light or water, essentially just enough to prevent the roots from drying out completely.

Remember to gradually acclimate your trees when moving them indoors or back outside. Sudden changes in light, temperature, or humidity can stress the plant. For instance, when moving trees outdoors in spring, slowly expose them to increasing sunlight over a week or two to prevent leaf scorch.

Harvesting and Enjoying Your Homegrown Fruit

The culmination of your hard work is the sweet reward of fresh, homegrown fruit. Knowing when and how to harvest ensures you capture the best flavor and extend your enjoyment.

Timing the Harvest:

The timing of harvest varies greatly by fruit type and variety. However, general indicators signal ripeness:

- Color: The fruit develops its characteristic ripe color. A green apple turns red, a lime turns yellow, a peach develops a blush.

- Softness/Firmness: Gently squeeze the fruit. Peaches, apricots, and many plums soften slightly when ripe. Apples and pears remain firm but feel less rock-hard.

- Ease of Separation: Ripe fruit often separates easily from the branch with a gentle twist and lift. If you have to tug, it likely needs more time.

- Taste and Aroma: This is the ultimate test. A ripe fruit emits a distinct, sweet aroma and tastes delicious.

For most fruit, harvesting is a process, not a one-time event. You will pick fruit over several days or weeks as individual pieces ripen. This allows you to enjoy a continuous supply.

Harvesting Techniques:

- Gentle Handling: Always handle fruit gently to avoid bruising, which reduces storage life.

- Twist and Lift: For apples, pears, peaches, and plums, gently twist the fruit upwards. If it is ready, the stem will detach cleanly from the branch. Try to leave the stem attached to the fruit if possible, as this improves storage.

- Snip for Figs/Citrus: For figs and some citrus, use clean pruning shears or scissors to snip the stem, leaving a small piece attached to the fruit. This prevents tearing the fruit or damaging the branch.

- Blueberries: Pick individually when they turn fully blue and release easily.

- Mulberries: Wait until they are dark, plump, and fall easily into your hand.

Storage and Enjoyment:

The best way to enjoy homegrown fruit is fresh off the tree. However, you can extend your harvest:

- Refrigeration: Most ripe fruit, especially berries and stone fruit, will last longer in the refrigerator.

- Countertop Ripening: Some fruit, like pears, benefit from a few days on the counter to fully ripen after picking.

- Preservation: Consider preserving excess fruit through freezing, canning, or drying. This allows you to savor your harvest long after the season ends.

Remember that dwarf fruit trees often produce a manageable amount of fruit, perfect for personal consumption and sharing with friends and family without overwhelming you with a huge harvest.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much fruit can I expect from a dwarf fruit tree in a container?

While yields vary by tree type and age, a mature dwarf apple or peach tree in a 25-gallon container might yield 10-20 pounds of fruit annually. Smaller trees like blueberries or dwarf figs can produce several pounds each. The specific variety and your care regimen directly impact the amount of fruit your tree yields.

Do I need to repot my dwarf fruit tree? If so, how often?

Yes, you need to repot your dwarf fruit tree as it grows. Start with a 10-15 gallon pot for a young tree, then typically repot every 2-3 years into a larger container, moving up to a final size of 25-30 gallons or more. This provides fresh potting mix and more room for root development. When repotting, gently prune some of the outer roots to encourage new growth.

Can I grow dwarf fruit trees from seed?

While you can grow fruit trees from seed, it is not recommended for reliable fruit production. Trees grown from seed are rarely true to the parent plant, meaning they may not produce the same quality or type of fruit. They also take much longer to fruit, often 7-10 years, and will not have the dwarfing characteristics provided by specific rootstocks. Purchase grafted dwarf trees from reputable nurseries for best results.

My dwarf fruit tree flowers but does not produce fruit. What could be wrong?

Several factors can cause a lack of fruit set. The most common reasons include insufficient pollination (if your tree requires a pollinator and you only have one tree, or if pollinators are scarce), late spring frosts damaging blossoms, or inadequate sunlight. Ensure your tree receives at least 6-8 hours of direct sun daily and consider if it needs a compatible pollinator nearby. You can hand-pollinate with a small paintbrush if natural pollinators are absent.

How do I know if my dwarf fruit tree is getting enough sunlight?

Observe your patio or balcony throughout the day. Track how many hours of direct sunlight the area receives. Direct sunlight means the sun’s rays are shining directly on the plant, not filtered through a window or tree canopy. If your tree is not thriving or flowering, lack of sufficient sunlight is a likely culprit. Most fruit trees require a minimum of six hours of direct sun for good fruit production.

For research-based guidance on edible gardening, visit Cornell Garden-Based Learning, UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions, Penn State Extension — Gardening, and Royal Horticultural Society on Growing Fruit in Containers.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice. Consult local extension services for region-specific recommendations.

Leave a Reply